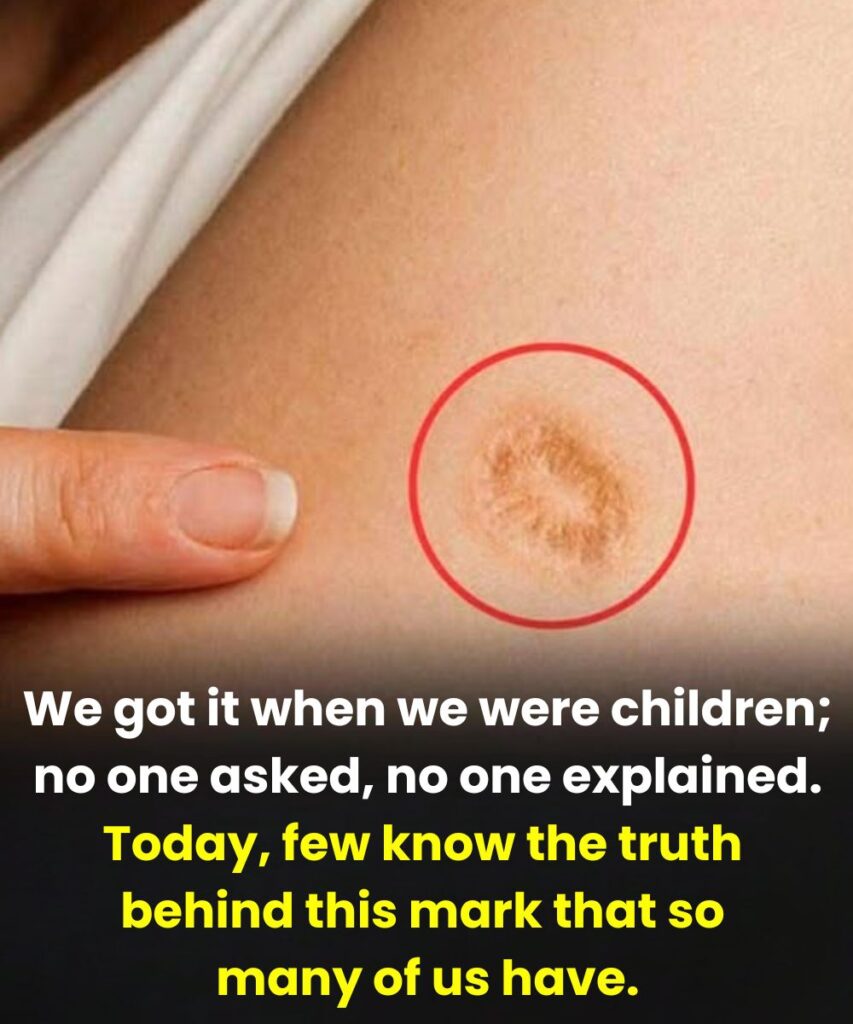

If you grew up in Asia, Africa, Latin America, or parts of Eastern Europe, there’s a strong chance you carry a small, round scar on your upper arm. Many people only really notice it as adults—while changing clothes, at the beach, or after someone points it out. For some, it’s a curiosity. For others, a source of embarrassment. And for many, it’s a mystery that was never explained.

That tiny circular mark has fueled confusion, assumptions, and quiet myths for decades. People speculate, invent stories, or associate it with things that simply aren’t true. In reality, the scar has a clear medical origin and a much larger story behind it. Understanding what it actually represents helps strip away stigma and replace it with context.

Below are five of the most common misconceptions about the round scar on the upper arm—and the facts that explain it clearly and honestly.

One of the most widespread beliefs is that the scar came from a childhood injury or a skin disease. Some people assume it was the result of an infection, a burn, or a wound that healed badly. Others remember falling or being hurt as a child and connect the scar to that moment.

In reality, the vast majority of these round scars are caused by the BCG vaccine, which was widely administered to protect against tuberculosis. The vaccine was typically given in infancy or early childhood, which is why most people have no memory of receiving it. The mark forms because of the body’s immune response to the vaccine, not because something went wrong or because the skin was damaged by accident.

The process is intentional. The vaccine triggers a localized immune reaction under the skin. As it heals, a small scar can form. It’s not a sign of injury or infection—it’s evidence that the immune system responded exactly as expected.

Another damaging misconception is the idea that only people from poor, rural, or disadvantaged backgrounds have this scar. In some cultures, the mark has been unfairly associated with poverty, poor hygiene, or lack of access to modern healthcare.

This belief is not just incorrect—it’s deeply misleading. The BCG vaccine was part of national immunization programs in dozens of countries, often administered universally regardless of income level or social status. Children from wealthy families, middle-class households, and rural villages alike received it. The scar reflects public health policy during a time when tuberculosis was a major threat, not personal circumstances or family background.

Having the scar does not say anything about education, class, or upbringing. It simply means you were born in a place and time where preventing tuberculosis was a public health priority.

Some people assume the scar functions as proof of vaccination. They compare arms with siblings or friends and conclude that whoever lacks the scar must not have been vaccinated.

That assumption is flawed. Not everyone who receives the BCG vaccine develops a visible scar. Some people heal without leaving a mark at all. Others may have had a scar that faded significantly over time, especially as skin changes with age.

The presence or absence of a scar does not indicate whether someone was vaccinated, nor does it reflect how well the vaccine worked. Immune responses vary from person to person. Two people can receive the same vaccine and heal in completely different ways.

Another persistent fear is that the scar signals something wrong with the immune system. Some people worry that it means their immunity was damaged or weakened, or that it represents a lingering vulnerability to illness.

The opposite is true. The scar is a sign of a normal immune response. The body recognized the weakened bacteria in the vaccine and reacted locally, creating inflammation that eventually healed into a small mark. This reaction does not harm the immune system. It does not reduce immunity or create long-term health risks.

In fact, some research has suggested that early-life exposure to certain vaccines may help “train” the immune system in beneficial ways. Regardless of those broader effects, the scar itself has no negative health implications. It is not a warning sign. It is not a weakness.

Because of lingering fear or cosmetic concern, some people believe the scar is dangerous or abnormal and should be removed. They worry it could turn into something harmful or that leaving it untreated is risky.

There is no medical reason to remove a BCG scar. It does not grow, spread, or transform into a disease. It does not require monitoring or treatment. Doctors consider it a benign, stable mark on the skin.

Removal is purely a personal cosmetic choice, not a medical necessity. For most people, the scar remains unchanged throughout life—a quiet, harmless reminder of early preventive care.

What makes this scar so emotionally charged is not its physical presence, but the silence around it. In many countries, vaccines were administered routinely, often without explanation to the child and sometimes with minimal discussion even with parents. The priority was protection, not storytelling.

As a result, millions of people grew up with a visible mark on their body and no context for it. In the absence of information, myths filled the gap. Shame replaced understanding. Assumptions hardened into false beliefs.

Learning the truth reframes everything. The scar is not a flaw. It is not evidence of hardship or neglect. It is not something to hide or explain away. It is simply a trace of a public health effort that saved countless lives during a time when tuberculosis was far more dangerous and widespread.

Sometimes the smallest marks carry the longest histories. That round scar on the upper arm is one of them.